Meditation 101 – The complete meditation guide

Meditation is a word which has been seeing increasing use and popularity over the past few years, and now we find it almost everywhere, in a large variety of contexts, and, above all, with what seems to be a lot of diverse meanings, definitions, purposes, and benefits.

They tell us it is good to reduce stress and anxiety, that it calms down the mind; that it is good for our health, that it reduces blood pressure and cortisol levels, increases longevity, and repairs and improves the brain; they tell us it is a way to get insight into ourselves and our own minds, to transform the way we feel, think, and behave, or to heal our emotions; it is a way to focus the mind, or it is way to dull the mind; a path to find true happiness and purpose; that it is not religious; that it is religious; we hear that it is simply a training of the mind, and then also that it is connecting to our deepest consciousness, to the energy of the universe, to our spirit, or to god; some will say it’s a way to attract what we want more of in life – more money, more success, more love –, while others explain it’s a way of transcending ourselves, releasing the ego, attaining Nirvana. They tell us meditation is the next big thing, the remedy for all our problems, the ultimate level of being; and they tell us it is just an invention, a waste of time, a superstition, or a scam.

No surprise that meditation is a word that brings confusion, mistrust, even controversy. But what is it, really? As we hear more and more about meditation, it becomes increasingly more important to understand what it truly is, where it comes from, why do people meditate, how it is practiced, and which are its real benefits and what it can in fact do for us. This article intends to be a clear, complete, and detailed guide on the definition, origin, history, purposes, methods, and everything about meditation.

What is meditation?

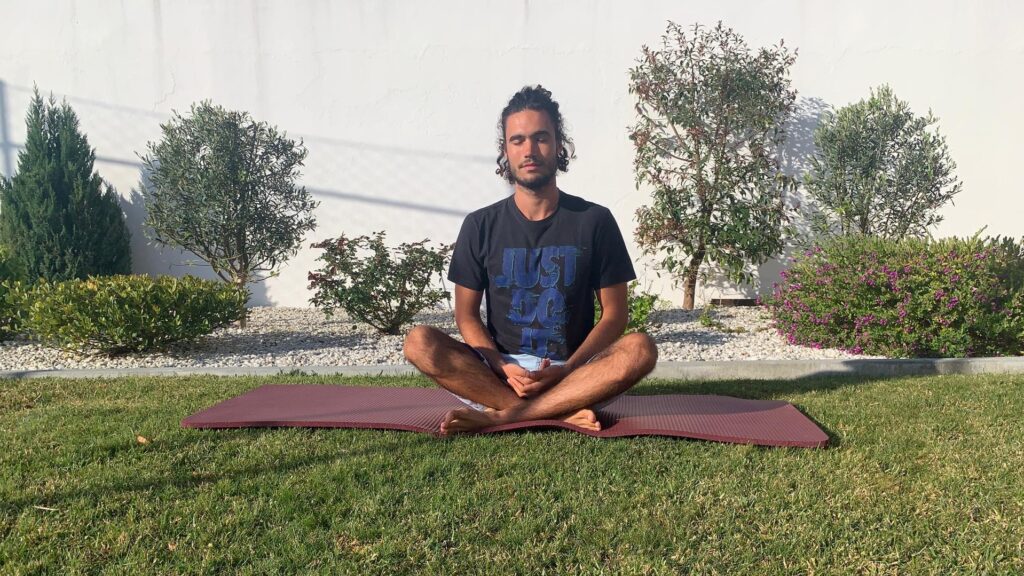

When you think about meditation, what comes first to your mind? Perhaps an Indian monk in a maroon rob sitting cross-legged in his lonely cabin in the Himalayas, with his hands on his legs, his back straight, his eyes closed, and his fashion relaxed and serene. But what is he doing? Is meditating just sitting very quietly and still for a long period of time doing nothing?

Well, it might be, as long as that “doing nothing” is intentional, voluntary, and consciously sustained. But that is just one of the many things he might be doing (or not doing) in his meditation. He may also be mindfully attending to his breath, stabilizing his mind; investigating his own physical and mental experience, getting insight into the nature of reality; cultivating in himself wholesome qualities, such as heartfelt love and compassion for every living being; engaging in analytical thought over a specific subject, idea, or situation; and countless other possibilities. All of these can correctly be called meditation.

He also does not need to be sitting like that – he could be sitting on a chair, lying down, or on his knees. And he even does not need to be still: he could be walking, stretching, or even dancing. He doesn’t need be wearing his monk robs – he could be dressed just like you or me, like a businessman, like an Arabian prince, or simply naked (in the Himalayas that’s ok). And, needless to say, it doesn’t have to be a he – it could be a she, or none of these.

Still, all of these are effectively called meditation. Why? What do they all have in common? What are the defining characteristics of meditation? I have already given you a giant hint, but in case you missed it, let’s take a look together.

Think about it yourself for a moment. What do you find in common in all the examples above, which may qualify them as a form of meditation? In all and each of them, the monk is doing something in or with his mind. They all seem to aim at achieving some state, some quality, change, or transformation to it. And, and this is key, they are all intentional, voluntary, and consciously enacted (that was the hint!).

With these set of characteristics, we can begin to grasp an understanding of meditation, or at least its core defining aspects. It is something that is done – an action or activity. It aims at doing something to or with the mind – achieving a specific state, cultivating a quality, reaching an understanding. And it is conscious and intentional. If we put it all together, we arrive at a very simple but remarkably accurate definition of meditation: Meditation is the act of consciously and purposefully shaping and transforming the mind.

This may come as an oddly too simple and straightforward definition of meditation, compared to all the buzz and fuzz we often hear about it. But it is the purest and most rigorous, authentic, and foundational one. Then, as meditation is spread and used by so many different people, with such diverse purposes, and in such distinct contexts, it can acquire special meanings and unique interpretations to those people. On occasion, some may come to believe theirs is the correct and only one, and maybe even try to persuade others on believing the same (kind of like the story of the blind men and the elephant). Yet this is its core, unadulterated meaning: the conscious and purposeful transformation of the mind. And it beautifully hints at its fundamental practicality and universality.

This understanding allows us to see meditation as tool or technique at our (and truly everyone’s) disposal to deeply change and transform the way we feel, think, behave, and the way we are – hopefully for the better. And that’s just what it is! It is not religious, mystic, or superstitious. It is not a complicated or hard to understand concept. And it is not one of its particular applications, methods, or practices. Meditation is a tool at the reach of us all to understand, transform, and improve our minds and ourselves – indeed, it is the very act of doing so.

“Meditation is a tool or technique to shape or transform the mind.”

– H. H. the XIV Dalai Lama

Origin and Etymology

One of the reasons meditation might be a confusing or ambiguous word is the myriad of different contexts and cultures it is found in and comes from. In fact, we can find it in nearly every culture and religion of the world, in different forms and often with different names, from East to West, including Buddhism, Hinduism, Christianism, Islamism, Sufism, and more recently secularism and Western science and medicine. So it becomes fruitful to comprehend where it comes from and how, its origin, history, and evolution over its birth, spread, and development in humanity.

The word “meditation” itself is our first problem here. It was a word which already existed with a different meaning, that was reused and adapted to denote this concept which had no previous translation to English and most Eurocentric languages. Its original meaning is the one we still currently find in the dictionary: “continued or extended thought; reflection; contemplation.” This is a noticeably different definition from the one we arrived at. As we understood, meditation may involve analytical thought or reflection, but it doesn’t need to and often does not, and it certainly is not it. Meditation is the conscious and intentional training and transformation of the mind, whether it involves thought or not (more on the different types of meditation below).

But that was its original meaning, before the word was used for this, and it is still frequently used with this sense nowadays. This double significance may be an important source of confusion and misunderstanding to people trying to understand what meditation is, so I hope this helps clear it out.

It is, however, interesting, that as we track back into the word’s origin and etymology, we approach more and more the meaning of meditation as we are using it here. It comes from the Proto-Indo-European root “med-”, which signifies the act of paying attention to, taking care of, working on, or correcting or healing something. This comes much closer to what we mean by purposefully training and transforming the mind – which truly is about paying attention to the mind, taking care of it, working with it, and correcting, healing, and improving it! I also find it striking that that is the very same root of medicine. Medicine is the care for the health, balance, and well-being of the body; and meditation is the same for the mind. (Thankfully, medicine is beginning to take more into consideration the mental side of well-being, and to that I believe it will take great benefit from welcoming and integrating meditation.)

Now, as noted, only more recently has meditation began to take part and be used in the Western or Eurocentric civilization, while it has been around and prominently present in other cultures, especially in south Asia and mainly in Buddhism and Hinduism. There is no doubt that meditation has arisen independently in many different places and cultures all over the world throughout human history, but it is also undisputed that southern Asia is one of its main birthplaces and sources of development and expansion. The Hindus had already been meditating for thousands of years when Buddhism was born more than 2500 years ago, having since greatly expanded and developed meditation. Our word “meditation” was used to translate this concept which has been part of their language for nearly as long as the culture itself. So what do they call it?

One of the most ancient words associated with meditation in these cultures is the concept of Dhyana in Sanskrit, Jhana in Pali, Chan in Chinese, and Zen in Japanese. Although its broader meaning is meditation as we have defined it, it directly translates into “concentration”, which is an essential part to meditation but not the same.

Another Sanskrit word for meditation is Bhavana, and this one is much more to the point. It was first coined in this sense by Siddhartha Gautama, also called the Buddha, and it literally means cultivation. Yes, cultivation in the sense of tilling and working on the land so that it brings a good harvest. Cultivation in the sense of bringing into being, nurturing, taking care. When Gautama chose this word, he was most probably referring to how meditation is the practice of working the mind, taking care of it, and planting the seeds to bring about beautiful and healthy results. And it implies that meditation is (or should be) a down-to-earth, everyday, and central part of our lives.

Glenn Wallis writes: “A farmer performs bhavana when he prepares the soil, plants seed, and protects and nourishes the seedling. When the sun shines, when rain falls, and when the temperature remains just so, that, too, helps to nurture the seed. Cultivated in this fashion, the seed becomes a beautiful, vibrant, and health-giving plant. This is bhavana.” And adds: “I imagine that when Gotama, the Buddha, chose this word to talk about meditation, he had in mind the ubiquitous farms and fields of his native India. Unlike our words ‘meditation’ or ‘contemplation’, Gotama’s term is musty, rich, and verdant. It smells of the earth. The commonness of his chosen term suggests naturalness, everydayness, ordinariness. The term also suggests hope: no matter how fallow it has become, or damaged it may be, a field can always be cultivated – endlessly enhanced, enriched, developed – to produce a favorable and nourishing harvest.”

Yet one more word which translates to meditation is the Tibetan Gom, which literal translation is “familiarization”. Familiarization, of course, in the sense of approaching, connecting to, and understanding our minds. But much more than that, it is familiarization in the sense of becoming familiar with, or habituated to, a way of being.

Most of our actions, behaviors, thoughts, and feelings are recurring patterns in us, automatic, because they are what we are used to. They’re how we usually define people’s personalities – the habitual way they behave, respond, think, and feel. They are our habits, and they are very hard to change – we act and, in truth, we are in the way we are familiar with.

Thus, if we want to change, and become a better or happier person, we need to habituate ourselves to a new way of being, and create new mental habits. We must familiarize ourselves with how we want to become. That is the true meaning of familiarization and meditation, and the way we can change and transform ourselves. This also implies a crucial notion of meditation that we will discuss in the next section, which is that meditation is not a magic spell or a quick fix, but rather a process, requiring time, repetition, and consistency.

The fact that meditation has arisen primarily in spiritual or religious contexts might leave you believing it is religious itself, but that is far from true. It has never belonged to any culture or tradition, and although it can be used for spiritual or religious purposes with great potential, it is not religious itself! It is a tool or technique which makes part of us all, and can be applied by anyone desiring to transform and improve him or herself and flourish as a human being.

In fact, meditation has been seeing more and more use in the Western secular (non-religious) context, with many practices having been adapted to it, and has begun receiving a meaningful place in fields such as medicine, psychology, neuroscience, and education. And, to be accurate, in its origin and early days, meditation was not seen as something religious, but as a path of self-discovery and improvement. For example, Buddhism was not a religion nor was it meant to be one, but a practical set of counsel with the aim of reducing unnecessary suffering, leading a meaningful and genuinely happy life, and achieving our highest and most beautiful potential; and meditation was therein seen as the fundamental tool that allowed us to actually do so. Meditation has always been about the transformation and flourishing of the mind and oneself.

How does meditation work?

Now, we know what meditation is, but how does it really work? How is meditation practiced, and how does it transform the mind? And is it not a waste of time? Does it actually bring about any transformation, can it truly help you change and improve? How so?

Sometimes we don’t believe we or others can change. We believe we are stuck with our way of being and that there’s nothing we can do about it, saying things like “it’s just the way I am” or “you can’t teach an old dog new tricks”. The truth is, changing often feels very difficult, not to say impossible, especially in what concerns those old and entrenched patterns in us. But we, humans, have an immense potential for change and transformation, often hidden behind limiting beliefs like these. Meditation allows us to tap into that potential and actualize transformation, even the most profound one. But how?

You might have begun to get a grasp of the answer from the discussion above on the original words for meditation and their meanings. Meditation works by unlacing old habits of the mind and creating new ones. With consistency and repetition, we habituate or familiarize our minds with a certain quality or skill, becoming better and stronger at it, and making it more natural and consistent in us.

Meditation is like a training – it is in fact a training of the mind. Just like we can train to become a skilled piano or tennis player, and go to the gym regularly to make our biceps bigger and stronger, we can steadily increase our capacity for attention, wisdom, and love and compassion by training. This training is meditation.

We can ask ourselves – how did we become who we are? Why do we think, feel, speak, and behave how we usually do? Where did we get our personality from – how did it form? Personality is defined as our habitual patterns of thought, feeling, and behavior – so, it was created by the way most usually think, feel, and behave. When we think, feel, or behave in a certain way, our brain learns it, becoming more likely to repeat it next time. Then, the more we repeat it, the more we learn it, the more it becomes part of us, our personality, automatic. And in turn, we become even more likely to do, think, or feel that in the future. This is how our way of being, our typical patterns of thought, feeling, and behavior, the good and the bad ones, have formed. It is how we became who and how we are.

The problem is, most of our living has been on autopilot mode, heavily conditioned and influenced by external causes and conditions. We have become who and how we are not by voluntary and conscious choice, but by hand of conditioned and automatic patterns. Much less, were they based on wisdom and understanding of what qualities and skills actually lead to and uphold genuine happiness, balance, and well-being, but rather most often on delusion and ignorance. Of course, our minds naturally have many afflictions!

Meditation is about doing the opposite. Meditation is the conscious, intentional, and (hopefully) wisdom-based shaping and transformation of the mind. It works the same way – by habituation and familiarization – except this time that which we are habituating to or cultivating is consciously and purposefully chosen and done. It’s like taking the plane off from autopilot mode and taking the wheel to control its direction and its path.

This is how meditation works – we consciously and voluntarily direct or shape the mind to the skills we want to develop, the insights we would like to reach, and in the way we wish to become, and away from those we don’t. Ideally, these are based on ethics and wisdom. With repetition and consistency, our mind is trained, habituates, and familiarizes with these, establishing new patterns and removing old ones. This is how transformation is achieved by meditation.

The difficulty of meditation

Meditation can be at the same time extremely simple and quite difficult. The difficulty comes from one main reason: that old habits are hard to change (that’s why they’re habits!). Our minds are naturally lazy, and don’t like to change the way they usually work if that is not necessary. Therefore, we encounter a natural resistance when trying to make any transformation or develop any quality or skill in meditation.

Habits are hard to change and this is one reason meditation can feel hard, especially at the beginning. Transforming them requires effort, which means that meditations requires effort to achieve any real transformation. But with the right motivation, that effort will not constitute a problem and transformation will happen.

Besides effort, meditation also requires time. Think about it – how long did it take these habits and patterns to form and become established? Months, years, even decades! Just like it took time to form them, it will take time to undo them and form new ones. So, one cannot reasonably expect to eliminate and get rid of them, as well as to create new ones, in just one or two hours of meditation. Transformation and growth take time! Meditation, when correctly done, taps into our extraordinary capacity for change, greatly reducing the time it would normally take. But still, it does take time.

At last, in order for meditation to create any meaningful transformation, we also need to make it consistent. We may think that the results of meditation come from a sum of the times we meditate, but that is wrong and misleading. Because when we are not meditating, we are still training and transforming the mind, although usually unconsciously and unintentionally. And if during this time we are thinking, feeling, and behaving in the same way as usual, then the half or one hour of meditation that we do per day will be no competition for the remaining 23 hours, and meditation will produce next to no results. If we want meditation to work, we need to both make it a consistent practice, and to actively try to bring about change even outside formal practice, during ordinary daily living, in that which may be called informal meditation.

Meditation is a job much like that of a farmer or gardener, where care and effort are given over time to create and nurture the seeds that will sprout and flourish in their due time. It is not about forcing the mind to become how we want it to, cracking the whip, being harsh or beating it up. We won’t make a sapling grow by pulling on it, or by throwing acid on it to punish it when it doesn’t grow as we want it to. Likewise, we can’t change or improve by forcing, much less with anger, frustration, or self-loathing when it doesn’t go as well or as fast as we want to. We must nourish and care for it with love and patience, and allow the mind to grow at its own pace.

We have seen that meditation is a training. And that fact also means that, just like any other training, it requires time, dedication, and consistency. You won’t get the results from day to night, just like you won’t become strong or fit after one single visit to the gym. Meditation is not some kind of magic spell, and also not a quick fix, something that only temporarily treats or hides the symptoms without addressing the root underlying causes. It is a true and profound transformation, and those are not done in the blink of an eye nor by only scrapping the surface.

But, if we give it the necessary dedication, time, and consistency, we can change even the deepest and most entrenched patterns, and bring about a beautiful and profound transformation in ourselves.

Science and meditation

There has recently been an increasing interest and inclusion of meditation by science. Considerable studies have been done regarding the effects of meditation in fields from health and physiology, to brain and neuronal changes, to psychological and behavioral transformations, and both in beginner meditators as well as long-experienced ones. Although there is still a lot to be explored, as well as an unique opportunity for science to learn from contemplative practice and not just study it, interesting and important discoveries have already been made, and diverse benefits have been found to be effected by meditation, including some of the listed in the next section.

Perhaps one of the most insightful discoveries of science, in particular neuroscience, is neuroplasticity. Neuroplasticity refers to the brain’s capacity to change, for neurons to create new connections and pathways, and even to generate new neurons – a revolutionary discovery. Meditation has been found to produce measurable changes in the brain structures and their level of activation, in the kind and number of connections neurons make, and even in the number of neurons with the stimulation of the creation of new ones. Meditation seems to tap into and powerfully stimulate neuroplasticity, originating changes in the brain which have significant effects in qualities and skills such as the quality and span of attention, emotional regulation, empathy and care, and mood and well-being. This correlation of meditation with neuroplasticity and brain changes helps corroborate the transformative power of meditation.

There is a strong tendency nowadays to only believe that which modern, western, materialistic science has studied and proven. This is useful and important when it comes to healthy skepticism and avoiding misinformation, as long as we hold in mind that science can fail and has its limitations too. One of them, I believe, is in what concerns meditation. We don’t and shouldn’t need modern, western, materialistic science to come and prove that meditation works. That has already been done by thousands of meditators over thousands of years, and can be done and proven again by yourself, by first-person experience. Besides, there are many aspects of meditation that the current scientific method cannot measure.

I do believe, however, that science can bring new and useful insights into contemplative practice and its effects and further our picture and understanding of it, as well as the other way around – to learn and improve from it. So, I see the recent increase in interest and inclusion of the study and exploration of meditation in science with delight and enthusiasm.

Buddhist monk Matthieu Ricard with neuroscientist David Richardson before undergoing an EEG (left) and fMRI (right) while meditating.

Photo by: Jeff Miller; ©UW-Madison University Communications.

In conclusion, how is meditation in fact practiced? Very simply put, meditation is practiced by intentionally taking a part of our time especially and exclusively for it, paying attention to and connecting with our minds, and consciously producing, cultivating, and training the skills and qualities that we want to develop, over and over again.

It’s as simple as that – no more gimmicks or schemes, no complicated directions or whimsical definitions. In fact, it is so simple that it becomes plainly obvious that it can be practiced by anyone. The question is, now, what skills and qualities do we want to develop, and why.

Types of meditation

There are at least as many types and forms of meditation as there are uses and goals for it, plus all the different methods that exist for achieving each unique goal. Meditation can be used to transform in any way and develop mostly any skills and qualities. This means that meditation is not good or bad by itself – it is just a tool, and the way we use it dictates the results we will get.

In this guide, we will focus on those skills and qualities that enable and empower us to lead a happier and more meaningful life, and the relevant practices that aim at cultivating them. If you have read our guide on the keys for a happy life you know that they come down to three fundamental ones: a balanced attention and peaceful mind, wisdom, and meaning and good values. It follows that the practices and types of meditation can be grouped into these same three categories, according to what they aim at cultivating.

Perhaps the most famous type of meditation is the one aiming at cultivating stable attention and calming the mind. It is a set of practices that begin by voluntarily attending to a neutral object, usually the breath, and goes on stabilizing, refining, heightening, and unifying attention and awareness, while ever increasing the quality of ease and serenity of the mind, up until the stages of single-pointed awareness (samadhi in Sanskrit) and complete meditative quiescence. This body of practices and its result are named Shamatha in Pali and Sanskrit, which literally means “tranquility”, “serenity”, or “calm abiding”. It is in this group that the practice and skill of mindfulness (sati in Pali) – the voluntary and skillful direction of attention and awareness – fits in, being in fact an integral element to Shamatha.

The application of meditation for the cultivation of wisdom and attainment of insight is the other great family of practices, and is collectively known under the name of Vipassana (in Pali, or Vipashyana in Sanskrit). It concerns the precise first-person investigation of one’s own experience, mind and mental phenomena, and the nature of reality, everything in it, and our relationship with it. For that, it relies on the application of the refined awareness and precise attention developed in Shamatha to the careful examination of body, feelings, mind, and all phenomena, mainly through a set of practices called the four applications of mindfulness (satipatthana). Vipassana aims at reaching profound and life-changing insight on the nature of reality and the true causes of happiness and suffering.

A third group of meditation practices are those directed at the development and cultivation of good qualities of the heart. These are good basic human qualities such as love and compassion, and are crucial to a meaningful and fulfilling life. They are developed through familiarization and based on wisdom and insight. At the same time, they powerfully enhance the practice and cultivation of mental serenity and wisdom itself. There are four main qualities which are aimed to be developed, being considered the pillars of a good heart. They are called the four Immeasurables (Brahmaviharas), and consist of Loving-kindness (metta), Compassion (karuna), Empathetic-joy (mudita), and Equanimity (upekkha).

Meditation can also be divided into discursive and non-discursive meditation, according to whether it engages thought and imagination or not. Practices such as mindfulness and attention training are non-discursive, in that they don’t involve any kind of analytical thought or active imagination. Cultivation of the good qualities, for instance, is usually discursive, involving active imagination, as well as some (but not all) kinds of insight meditation which draw on analytical thought.

These are just the cornerstone and most beneficial types of meditation, keep in mind that each of the general types can have a multitude of different forms and practices fit into it. Likewise, there are plenty of forms and applications of meditation that do not fit in these categories, which are framed in other contexts and serve other purposes. There are even meditations that can be harmful! Here we have focused on the most essential and standard, and those that will bring you the most meaningful benefits and provide a path to of genuine happiness.

Benefits of meditation

There are as many possible benefits of meditation as there are ways to constructively transform and improve the mind and oneself. In reality, the actual benefit of meditation is the possibility to transform and improve our minds and ourselves. The benefits you get from meditation depend on how you use it, with what purpose, and how much time you devote to it.

The main and most important purpose and benefit of meditation is having a bigger possibility of choice in our lives, on who we are and how we act, to really be able to transform, develop and improve ourselves, to become better and happier persons, and to reach our true human potential.

The ultimate benefit of meditation is the realization of the nature of reality, our existence in it, and the true causes of happiness and suffering; and the liberation from or extinguishment of all kinds of mental afflictions. These are also known as “awakening” or “enlightenment” (bodhi in Sanskrit), and nirvana, respectively.

We can simplify it down to happiness and well-being, as long as we are talking about genuine happiness. Meditation’s basic goal and benefit is to live a good and happy life, for us and others around us. In specific, it allows us to develop a calm and peaceful mind with a balanced attention and refined awareness, to cultivate wisdom and get insight into the nature of life, reality, and happiness and suffering, and to live by meaningful values which provide the scaffold for a fulfilled life.

With this said, meditation can bring us many valuable and invaluable benefits along this path, the most relevant of which are listed below:

- Improved concentration and attention skills

- Decreased stress and anxiety

- Burnout prevention

- Improved emotional awareness and regulation

- Improved awareness and handling of others’ emotions

- Decreased reactivity and impulsiveness

- Increased choice in behavior and speech

- Increased resilience

- Improved mood

- Improved happiness, well-being, and fulfilment

- Improved self-esteem

- Improved health (lower blood pressure, blood sugar and lipids, enhanced immune system, skin, and more)

- Increased longevity

- Improved sleep

- Improved relationships (intimate, work, and casual)

- Improved connection with ourselves, others, and reality

- Higher capacity for empathy and care

- Increased productivity

- Change and transformation of destructive emotional, cognitive, and behavioral conditionings

- Profound healing of emotional wounds and trauma

- Valuable insights into the functioning of our mind, feelings, thoughts, beliefs, behavior, and relationships

- Valuable insights into the reasons for others’ feelings and behaviors

- Valuable insights into how reality and things work

- Valuable insights into the nature and causes of happiness and suffering

- Can help in the treatment or alleviation of mental conditions such as anxiety, depression, OCD, addiction, PTSD, and others

- Can help alleviate or better deal with chronic pain

- Much more…

These are all precious, and sometimes life-changing, benefits that meditation and its various forms and shapes can bring us to improve our well-being, emotions and mood, relationships, actions, and life. However, it is important to keep in mind that meditation is not a panacea, something like a miraculous solution to all the problems and difficulties of our lives and the world. It is a process that requires actual time and perseverance to achieve any palpable transformation. Besides that, there are some (many) problems which cannot be resolved simply by meditating – they require action –, and others that cannot be solved at all.

However, there are many problems (and I would say most of them) which underlying root is to be found in our minds – in our destructive tendencies. In fact, most of our suffering is entirely made up by ourselves, and our way of appraising and grasping onto the world and our sense of self. For all of these, meditation offers a profound path of self-discovery and transformation, and can serve not as a solution, but as a tool to bring about the solution to so many of our problems and so much of our suffering. To those problems which require action, it can help us prepare to better identify and take the right action. And to those that cannot be solved externally, it can become a path to restore mental balance and find peace inside.

Other questions and doubts

Here are the answers to some common questions you may still have about meditation:

Are meditation and mindfulness the same?

Mindfulness and meditation are not the same thing. As we explained in the “types of meditation” section, mindfulness is a specific skill which can be developed through meditation. It can also refer to a type of meditation – the one aimed at developing that skill. While meditation is the tool that allows us to train and develop mindfulness.

Because mindfulness has become so popularized and mediatic in the West, many have come to equate it with meditation, but that is completely wrong. Mindfulness is a very specific type of meditation, or more accurately, a skill developed in meditation and central to it. However, there is much more to meditation than mindfulness.

Also, it is important to note that what is meant by its popularized use in the West does not correspond to the original meaning and definition of mindfulness (sati). It has been changed to refer to one very specific function and application of mindfulness (continuous non-judging present moment awareness), aimed primarily at reducing stress, which, although undoubtedly useful and helpful for many people, unfortunately is a misconception and passes a wrong and very limiting idea of what mindfulness is.

(More in a future complete guide on mindfulness. Subscribe below to receive it!)

Are meditation and yoga the same?

In the first place, the traditional meaning of yoga is not the one we usually associate it with today. Yoga was the whole path of personal transformation and flourishing aimed at attaining liberation and enlightenment, of which meditation was the main pillar in its various shapes and forms. One of its elements was a set of physical practices, postures, and breathing exercises with the goal of developing physical and mental strength, called Hatha yoga (literally “yoga of force”). This could be effectively seen as a form of meditation, and is still practiced and taught in this way in many places. However, the “yoga” that has become most popular and widespread is a watered-down version of this Hatha yoga, but seen more exclusively as a form of physical exercise or relaxation, which is nonetheless very useful and important.

Are meditation and prayer the same?

Meditation is very distinct from prayer, at least its most strict definition. Prayer is usually defined as a direct dialogue with or appeal to a god or a divine entity or force. Another strong distinction is that prayer is nearly always considered a religious practice. However, broader definitions of prayer include the shaping of one’s mind to attain more profound and refined states of consciousness, connect with reality, reach insight, and even to cultivate qualities such as immeasurable love and compassion. That comes much closer to the meaning of meditation!

Is meditation religious?

Meditation is not religious, in that it is not inherently part of a particular set or tradition of practices and beliefs. Meditation is a transformational tool that can be used for varied purposes, including, but certainly not limited to, religious ones. Ideally, meditation is undertaken grounded in good values and ethics, and with the aim of becoming a better, wiser, and more balanced person, more capable of bringing genuine happiness to oneself and others. Whether you call that spiritual or not, it is up to you!

What kind of meditation should I practice / is right for me?

The meditation you should practice depends on your needs and goals. However, just like you need a balanced diet to stay healthy, it is recommended that you keep a balanced meditation practice to stay mentally healthy and flourishing, that includes the cultivation of good values and ethics, the training and refining of attention and awareness, and the realization of insight and wisdom. These forms of meditation are all an essential part of the path, and they all complement and support each other.

How often / how long should I practice meditation?

The more you practice, the more you can bring the most profound and meaningful benefits of meditation into your life. How much you practice depends on your goals and motivations, and should be adjusted to your possibilities and life conditions. If you are able to invest around half an hour every day, that would be already very valuable. If you can do more, that’s great! And if you can’t do as much, then do what you can, although in many cases I would suggest you to review your priorities. Afterall, our mental health and balance, genuine happiness, and flourishing are not (or should not be) trivial to us! Remember that consistency is key, and that also means bringing intentional transformation into our daily lives outside formal practice. Finally, the regular practice can be greatly enhanced by occasional periods of intensive practice, such as retreats.

Is meditation hard to do? Why am I not getting results?

Meditation is simple to do if you understand what you are doing. But it means training to improve a certain skill or cultivate a certain quality – it doesn’t mean being already able to do it. If that was the case, we wouldn’t need meditation for anything. Meditation is the act of training, of improving, and it only becomes hard when we mistakenly think it is the actual succeeding or achieving it. Then, we may think “I am meditating, so I should be able to do this. But I’m not, so I’m bad, or meditation is hard, or it doesn’t work for me”. Remember that meditation is simply the act of training, the cultivation. If you are doing it, you are succeeding, so you can see it is quite simple to do. The results and transformation will come with time and dedication.

Meditation requires times and effort, and is not about overnight results, instant gratification, a quick fix, or like taking a pain killer (maybe because it actually addresses the causes and not just the symptoms). While it is true that a single few minutes of meditation can truly make a difference in your day and well-being, that is only the scrapping of the surface. Take your time and you will see the change coming through. You might also not be getting results because you are not correctly addressing and doing meditation. In that case, it may be helpful to search for a good teacher.

Do I need a teacher / guide to practice meditation?

You do not need a teacher, especially if you have the right motivation and mindset. Still, an experienced and wise teacher may greatly benefit you and further and enrich your path, with helpful and insightful guidance, advice, and support. A teacher can help you better understand and navigate your mind, and your path in meditation, its steps and stages, its challenges and successes, its goals and its methods, and answer your personal questions and doubts. Plus, a substantial part of a teacher’s work is precisely helping you cultivate the right motivation and mindset. If you are looking to begin or improve your practice, then I would definitely recommend you to find a teacher, whether individual or in group, who can serve as guide, counsel, and support when you need it.

However, keep in mind that a teacher should only be just that – help, advice, and support – and not be the one to direct your path, tell you what to do, how to be, or what to think. Meditation is a unique path for each person, and only you can do it – no one can do it for you. You must be in the driver’s seat of your own practice, or meditation would be defeating its own purpose. So, remember to see your teacher as someone who can help you understand where you are and where you want to go, and aid you in your path from the former to the later.

If you are interested in finding a meditation teacher or guide, you may wish to look into our programs, or experiment an individual session.

I hope this guide has helped you accurately and thoroughly understand meditation, and answer your most important questions and doubts. If you still have any question, please ask it in the comments below, or you can just leave your very much appreciated feedback!

This guide is part of a full series on meditation, with many more to come. Stay tuned for more!

Comments